Richard Murff

Jul 23, 2024

The CrowdStrike bug illustrates just how vulnerable our world is.

Late last week, cybersecurity firm CrowdStrike managed to send out a nasty bug with its software update that made the company an instant metaphor for just how vulnerable our little internet of things is.

In the airline sector alone some 7,200 flights were canceled; Delta alone scrubbed 30% of its routes over the weekend. Microsoft customers are still sorting the mess out and it’s still in a weekend news cycle that includes an incumbent president bowing out of the race about a hundred days until go-time. The crash was a lot broader than the airline sector, but since it ruined the most weekends, let’s start there.

I’ve worked with a couple of airlines, their business models are, in essence ever-shifting logistics puzzles getting solved in real time as passengers and crews change nodes or exit the network. True, the carriers are pretty mellow when it comes to leaving you in Atlanta, because your connection flight is happy to take off without you. There are laws against flying without crew, though, so a surge in crew missing their connections causes more grounded flights, triggering a cascade of grounded planes throughout the system. And repeat.

Given the mêlée caused by a single, easily reversible bug in a software update on a single security platform, it bears considering exactly how vulnerability of critical US infrastructure is to a really nasty outage.

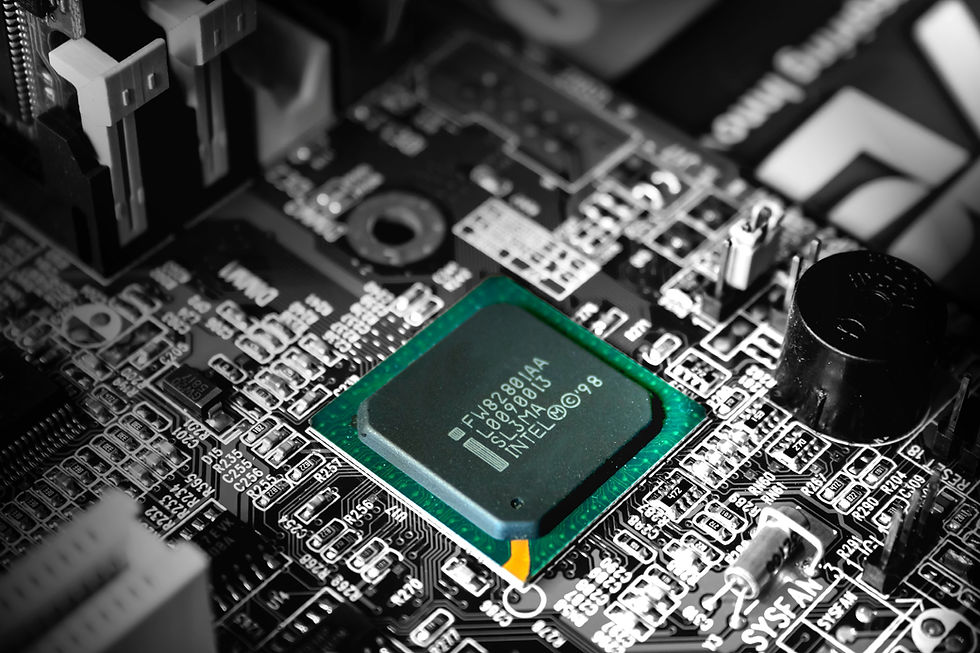

Our digital lives are pulsing along on a patchwork of computer software, electricity and signals that even the people who built it don’t entirely understand and the rest of us not at all. Our utter lack of human comprehension makes it very uncomfortable to consider what might happen when the whole thing simply blows a fuse. So of course, the 4717 is here to ruin your day with a timely insight on an electromagnetic pulse...or EMP.

EMPs can and do occur naturally. In March of 1989, a solar flare knocked Quebec off the power grid, with other outages in the Northeastern US. You can also trigger one. The pinch bomb the charming thieves in Ocean’s Eleven use to knock out the Las Vegas power grid exists – but doesn’t create a big enough EMP to knock out a cities lights.

According to the Air Force, though, you can trigger one that will really ruin everyone’s day. Per Capt. Ronald McKinney Jr. of the US Air Force, ““When a high-altitude nuclear detonation occurs, gamma rays from the explosion cause air molecules to ionize. This reaction produces positive ions and recoil electrons... The result is an extremely powerful electromagnetic field with the ability to damage or destroy electronic devices over a widespread area. The destructive capacity of such a magnetic field could wipe out large swaths of the technology-based critical infrastructure systems in the continental United States, putting millions of lives in danger.”

For about 20 years now, Newt Gingrich has been warning about the dangers of a weaponized electromagnetic pulse that will play hell with pretty much everything wired for electricity in its path. So, while we’re chewing on the implications of that Russian space weapon we can’t quite sort out, let’s consider a weapon that fries the electric wiring over large areas, but leaves buildings standing.

How much damage are we talking about? High-altitude nuclear testing during the 1960s demonstrated a one 1.4-megaton explosion had an estimated EMP blast radius of 800 miles. It knocked the power out in Hawaii, about 470 miles away. Stephen Younger – former head of the Defense Threat Reduction Agency, Los Alamos weapons designer and author of The Bomb, argues that a weaponized EMP wouldn’t necessarily fry everything. Its effects would be more random and temporary. Now I’m more inclined to believe a weapons designer over a politician, but his lighter assessment doesn’t get us out of the woods yet.

The Cascade

An EMP doesn’t have to take out all the power stations, just the right ones: The North America power infrastructure is rigged as networked grids; with power generators serving markets with wildly varied consumption. So a generator producing more than its local grid needs at a given time will send power out to other grids to meet higher demand where it’s needed. If the station isn’t generating enough power, it will draw on the network to meet demand. It’s a brilliant system that few of us would understand even if we thought about it, which we don’t.

Yet, take the example of a relatively minor power fluctuation in November of 1965, when power flowing from a Niagara Falls power station fluctuated high, tripping the circuit to the overloaded line. The power was re-routed across four different lines heading north. The unexpected surge then tripped the four lines as well, sending all that power flowing south in a huge surge across New York State which was humming along at full tilt at the time; it was cold, it was rush hour, it was New York. Within 12 minutes, a near complete blackout stretched from New Jersey across New York, Boston and north of Toronto. Like the CrowdStrike outage, it’s not the originating failure that’s the problem, the cascade.

If you live in Memphis, or elsewhere in the third world, your power goes out on fairly regular basis. But an EMP outage isn’t just the house; it’s the phone – everyone’s phone and well as the system that makes it work – landlines, internet, radio. Most likely your car is out of luck too.

Where ever you are going, you are going on foot. Don’t bother calling ahead.

Next come the abstracts: Massive data loss (be honest when was the last time you reconciled your bank account old school?) All those passwords you don’t know because your computer made them up and remembered them? Your computer just forgot them. But it doesn’t matter because the cloud in which we’ve placed out safety, has just blown away.

So... how likely?

Now that we’ve ruined your day, it is worth asking just how likely the scenario is: Not very. Or at least it wasn’t. You’ll need a medium sized nuclear weapon to start with, and then a way to get it 25 miles into the atmosphere to nice, big blast radius to really play hell with civilization. The players who can pull this off are limited. There is us, the French and the Brits – so let’s rule them out. India could, but it won’t. Iran would like to, and could do it to Tel Aviv, but not the US.

That leaves China and Russia. They have the means, and the motivation on a bad day, but it isn’t that simple.

Deniability:

Moscow and Beijing are directing all those cyper-attacks on infrastructure (and ours at them) to test creating the same mayhem and infrastructure disruption as an EMP, but do it with a bit of deniability. It’s hard to deny blowing up a warhead in a rival’s airspace. This would signal the start of a war.

Missile Defense Shield:

The US plan throughout the Cold War has always assumed that the first target would be against power infrastructure and communications. Essentially, we are prepared for this. If you’re first shot gets blocked, you’re well-nigh screwed because retaliation will be on auto-pilot. Leading us to the real bitch...

Retaliation:

Even if the first attack got through, the country’s nuclear arsenals are built to withstand an EMP, which means that whomever lobbed the first shot is still screwed. Neither China nor Russia can take us out with a single attack anymore that we can take them out. That’s the thinking behind Mutually Assured Destruction – any use of the weapon is a murder-suicide pact.

Should the strikes be limited in nature (a big if) the second order effects of the knock-on will be asymmetrical: A strike on the US is likely to turn what’s left of the country into a vast, cancer-ridden tribe of John Wayne knock-offs. A retaliatory strike against Russia will mean that regime will fall that week to a big, cancer-ridden mob. Big Panda over in Beijing might hang on a little longer, but remember, the Chinese are the ones with the surveillance state – he’s more dependent on the internet of things than we are.